59

“It was the ideal college job because I could

make them when I wanted to make them.”

In his career in this niche field, Paine

has used his broad knowledge of military

history to create pieces for private col-

lections, museums, and other large insti-

tutions, including the Franklin Mint. His

models and figures reflect his interest in for

the Napoleonic era, the Civil War, World

War I, and World War II (not to mention

fantasia, including a scene from

The

Hobbit

, and from famous works of art).

Jim DeRogatis, a fellow modeler who

recently released a biography of Paine,

calls him “arguably the best-known

military miniaturist in the world….He has

done more than anyone else to elevate

modeling to the level of an art form,

one that includes elements of painting,

sculpting, historical research, and vivid

storytelling.” An online biography of

Paine describes him as a “champion of

the diorama” who has written numerous

how-to manuals – and a handful of books

– for modelers and fellow diorama

enthusiasts.

“Shep’s biggest talents as a miniaturist

are imagination and storytelling,” says

DeRogatis. “For sheer technique, others

have been better painters or sculptors.

But Shep has been able to draw the viewer

into his work in a way that no one else

ever has matched, via the power of the

stories he told, much like a great direc-

tor in the theater or cinema, and the

unique and distinctive touches – whim-

sical, poignant, humorous, or pure imag-

ination that could keep you endlessly

glued to his pieces.”

Two artists, according to DeRogatis,

who have come close to but never ex-

ceeded the acclaim Paine garnered in

the field are California miniaturist Bill

Horan and Swedish artist Mike Blank,

who has been at the top of the field for

the last decade, since Paine declared semi-

retirement from the pursuit.

“But Shep really has occupied a singular

position in the hobby,” DeRogatis says.

“Think Beatles, Rolling Stones, and Elvis,

all combined.”

Paine describes his own work as detail-

oriented, both because of the care with

which he studies the figures and his close

examination of the periods in which they

lived. His passion for research has allowed

him to be an archaeologist of sorts, dig-

ging through history to reproduce every-

thing from expression to stance to “trying

to figure out what these people would

have in their pockets.” For his model of

Rembrandt’s

Night Watch

, he incorpo-

rated missing figures, which had been

cut from the painting when framed. But

even though his topics are serious, he is

careful not to take his work

too

seriously.

“It has been fun,” he says. “But I don’t

take it too seriously. Like anything, when

you start getting involved in the detail

work, you can start losing sight of the

forest through the trees. I hope I have

never lost sight of the forest.”

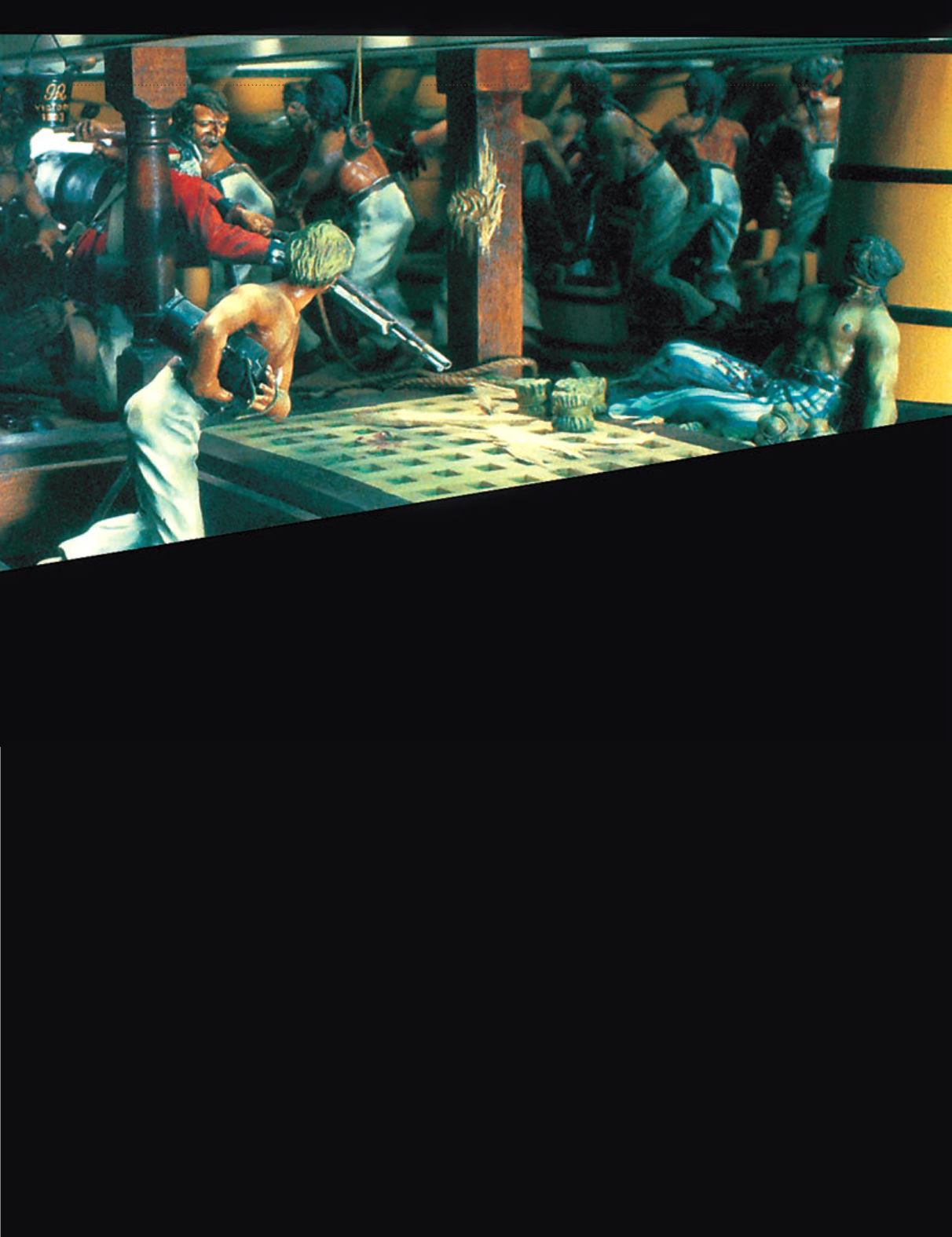

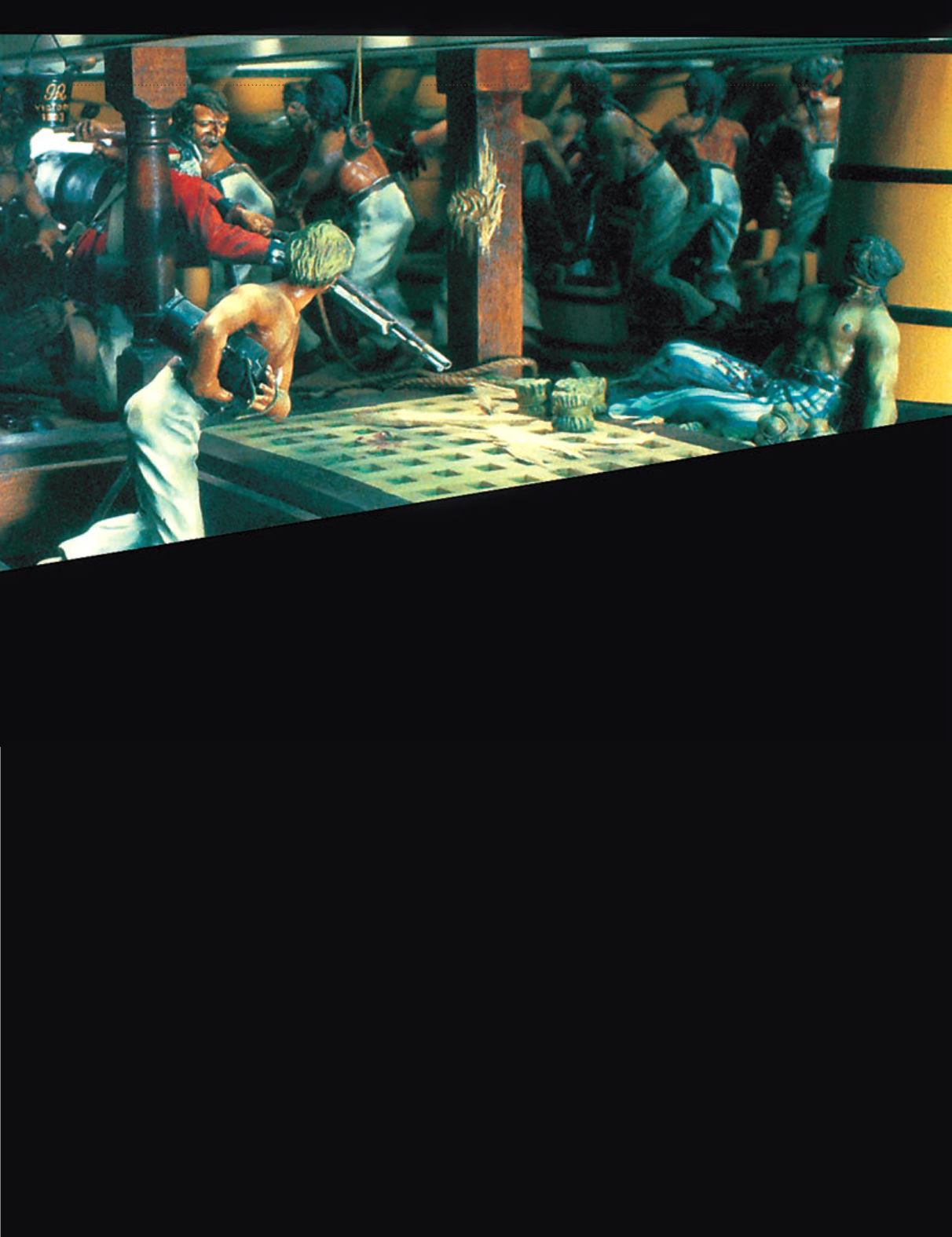

The gun deck of HMS

Victory

at Trafalgar, 1805