60

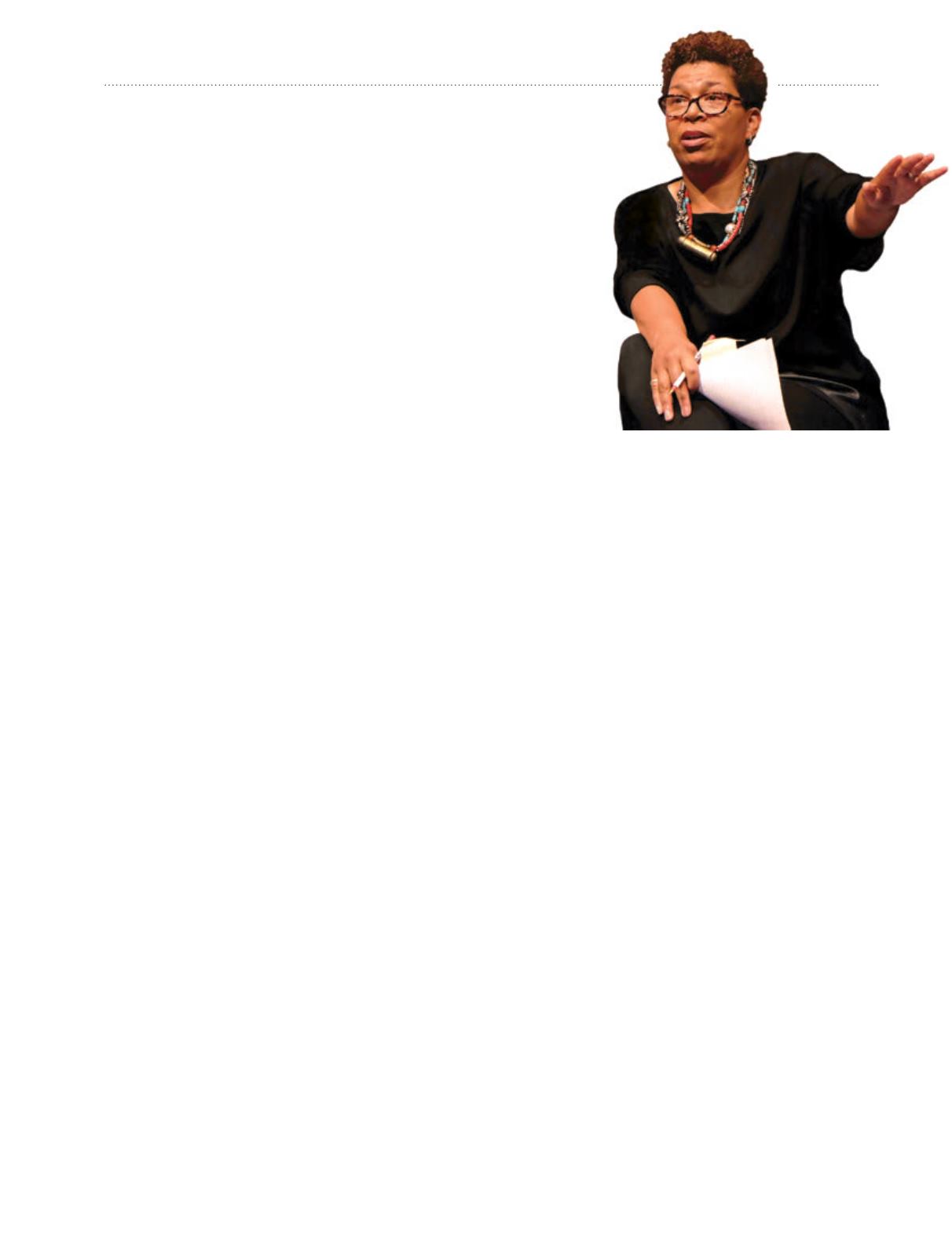

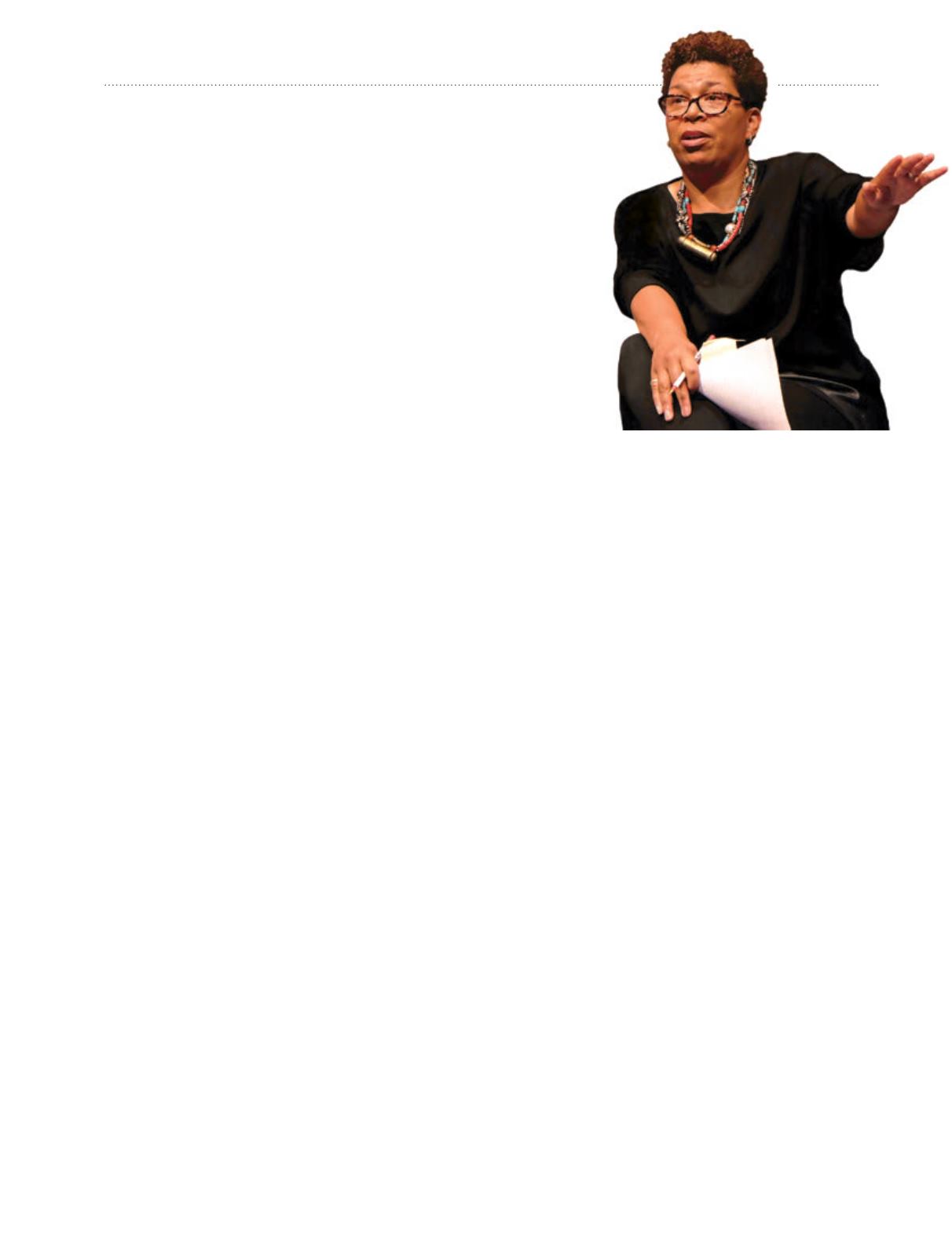

FACETIME

In the aftermath of the shooting of teen-

ager Michael Brown by a police officer

in Ferguson, Missouri, National Public

Radio’s Michel Martin ’76 was invited

by St. Louis Public Radio to moderate a

community conversation (“Ferguson and

Beyond”) in the shaken city. The two-hour

public event drew more than 200 people

to Ferguson’s Wellspring Church.

My role was to be a moderator, and it

was not a small thing.

St. Louis Public

Radio asked me to facilitate a community

conversation, and they made some critical

decisions. The first was to have the con-

versation at a church in the community

as opposed to at the radio station. The

critical decision [NPR] helped

them

make

was to be sure responsible people in gov-

ernment were part of the conversation.

It was not just young African-American

people who spoke up, but some of the

white constituents

– parents spoke up

and said we don’t like the way the whole

situation has transpired; we are equally

concerned. They said they don’t like that

this community is not safe for everyone.

The young [African-American] students

were not expecting to hear that. They

didn’t realize they had allies. That made

for some powerful moments.

I am not sure the mayor of Ferguson

understood that this was not just about

Michael Brown being shot and unarmed

,

but his body lay in the street for hours, in

full view of many, including his mother. I

don’t know that he understood the full im-

pact of that. I asked him if he was inclined

to apologize to Michael Brown’s parents,

and he said they had not approached him,

but he would consider it if they did. It was

an interesting experience in that people

had a chance to hear from neighbors in

a way they had not previously, and it was

the same for officials and constituents.

I thought it would be emotional, and it

was.

We came early to do reporting and we

saw the heavy police presence in Ferguson,

saw cars pulling people over aggressively.

There was one gentleman who said he had

$300 in jaywalking fines in a community

where there are no sidewalks. A lot of

black people felt they had been targets of

very aggressive policing.

People were upset and they exercised

their right to protest.

But there were

also people in the community who did

not appreciate the days of disorder, the

impact on local businesses, outsiders in-

stigating behavior that was not acceptable.

My role in this was to help us have a

good conversation, though we may

not agree on what that means.

I felt

that if people left feeling some truth had

been spoken, that everybody had been

heard, then it would feel worthwhile. I

feel we accomplished that and let people

express themselves in a way that was un-

comfortable – but necessary – for some

people to experience. The room was full

and everybody stayed.

One of the points a lot of people made

was that it wasn’t just about Ferguson.

I’m not sure people understand that there

are a lot of small towns where the bound-

aries are not always clear. We heard from

people who feel there is a really hostile and

antagonistic attitude between authorities

and people in the community. The lack of

diversity in the Ferguson Police Depart-

ment was visible, and there are no legis-

lators of color. The recently retired city

councilor said turnout in local elections

is low and asked people why they are not

participating. Where is their accounta-

bility in terms of participation in select-

ing the people who will govern their city?

The conversation was called Ferguson

and Beyond and that had dual mean-

ing.

The question is: What are people in

this particular community going to do to get

beyond this, now that the questions are on

the table? If people are not satisfied with

the answers from elected officials, what

are they going to do to hold themselves

and their community leaders accountable?

The conversation was broadcast in 26

cities, and the questions were relevant

to other parts of the country, too.

There

is a disconnect in how the people are served

by their leaders and what role they should

take in the governance of their own com-

munity. People need to participate in gov-

ernment so they have a standing to lodge

complaints.

One thing we have learned from this

event is that structures matter.

The

way people do their jobs matters. The

police chief in Ferguson apologized to

the family for the way Michael Brown’s

remains were handled. He had clearly

absorbed some of the hurt that had been

expressed and understood and heard it.

If you look at the issues in which

black and white people have very

strong differences of opinion, a lot

of it centers on law enforcement

.

Black people feel abused and that they

are treated with a lack of respect from

people who are there to protect them.

Relationships matter. How many white,

middle class people did not understand

how the black young people were routine-

ly treated in Ferguson? It was important

to understand there were other people

in the community who cared about

that. People

do

care about this, whether

or not they are directly affected by it.

How law enforcement conducts itself

does

matter.

I don’t yet have plans to return to

Ferguson, but I do have a desire to

go back.

A number of people from the

community have reached out to me and

asked me to come back. I am looking for

an opportunity to figure out what makes

sense.

Michel Martin ’76

AUGUST JENNEWEIN / ST. LOUIS PUBLIC RADIO