28

Captain FitzRoy took Darwin on the

Beagle

crew as a

gentleman with whom he could talk about science while

sharing meals in his cabin. The ensuing voyage around

the globe and the resulting theory of evolution changed

the world. The rest is history. But an important discovery

that eluded Darwin due to limitations in resources and

manpower in the mid-1830s was one that fascinated

me. Darwin’s initial path eventually led – more than 150

years later – to the unearthing of the most comprehen-

sive giant titanosaur fossils on record.

Dinosaurs have excited scientists – all mankind, really

– for centuries. Imagine a

carnivore with 62 serrated

teeth, six inches long in a

head seven feet long, pursu-

ing mammalian flesh. Picture

an enormous plant-eating,

lizard-like sauropod, 80-

plus feet long, weighing 20

tons and devouring every

bit of vegetation in sight.

These were the fellows who

roamed the world for more

than 150 million years. Our

Homo sapiens existence, as

we know it, has lasted ap-

proximately three million

years, and the only real

knowledge we have on the

subject of human existence,

but for pictographs, is 5,000

years old. We should be very

thankful for the extinctions of

certain animal forms, which,

in all likelihood, would have

by now gobbled us up or

slapped us to death with one

swish of a mammoth tail.

I confess an abiding interest

in finding dinosaur bones

as a hobby. I learned early on that one risks life and limb

by seeking – and finding – old bones. Nations contest

for such fossilized relics, just as bone hunters of the Wild

West in the late 1800s clashed during the Bone Wars. In

2012, an auction of an 80-percent-complete articulated

tarbosaur, a T-Rex-type, brought Mongolia and the United

States into play, involving the Customs Department, the

Justice Department, and the Bureau of Homeland Security.

I know; I was the winning bidder at the auction, trying to

get the bones to the Peabody Museum at Yale University.

I almost got thrown out of the Society of Vertebrate Pale-

ontology for it, as the Society didn’t know I was bidding

for the Peabody Museum, but I happily remain a member

in good standing. The prior largest auction ever brought

more than $8 million for a T-Rex, proving that bones

invoke more than scientific interest alone.

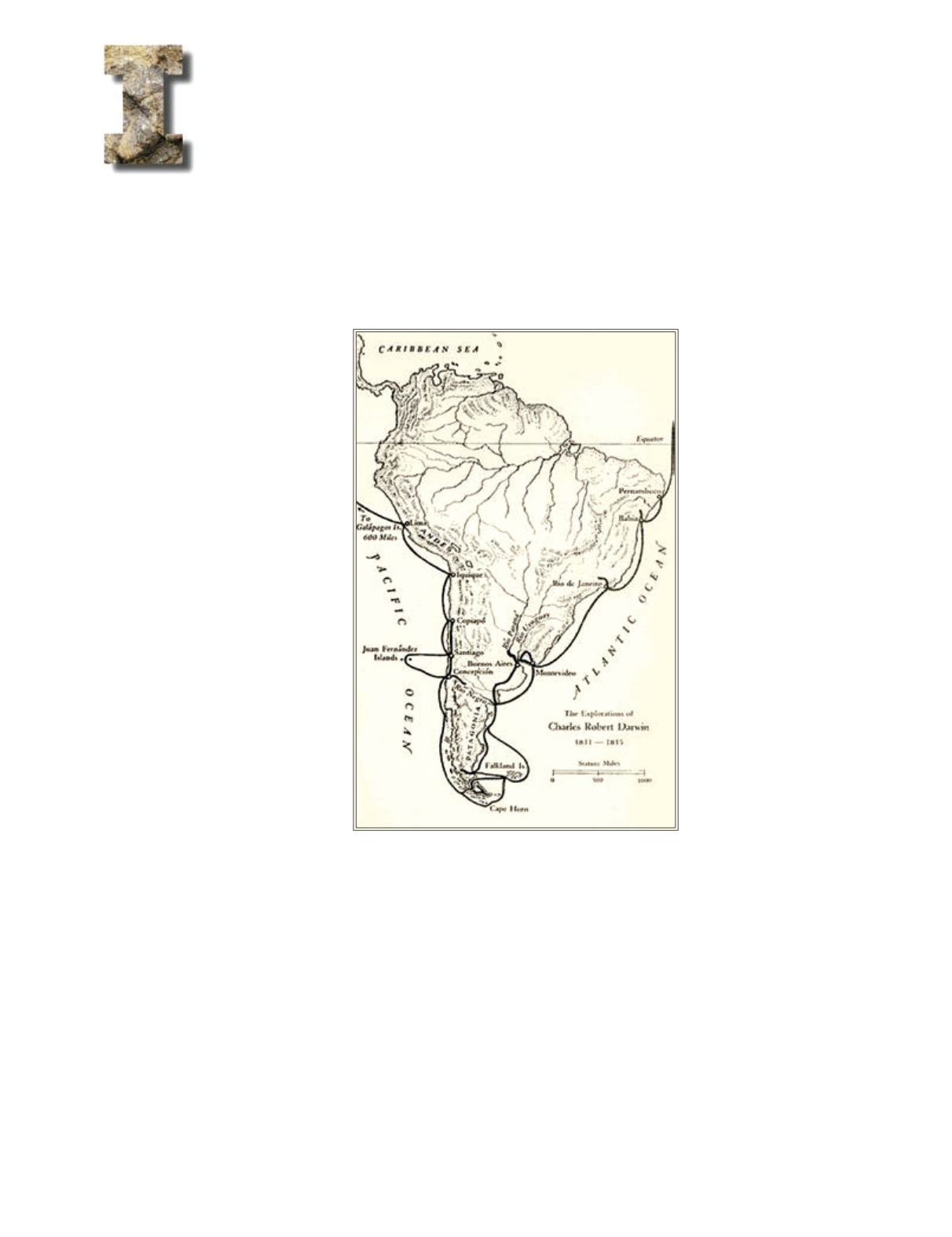

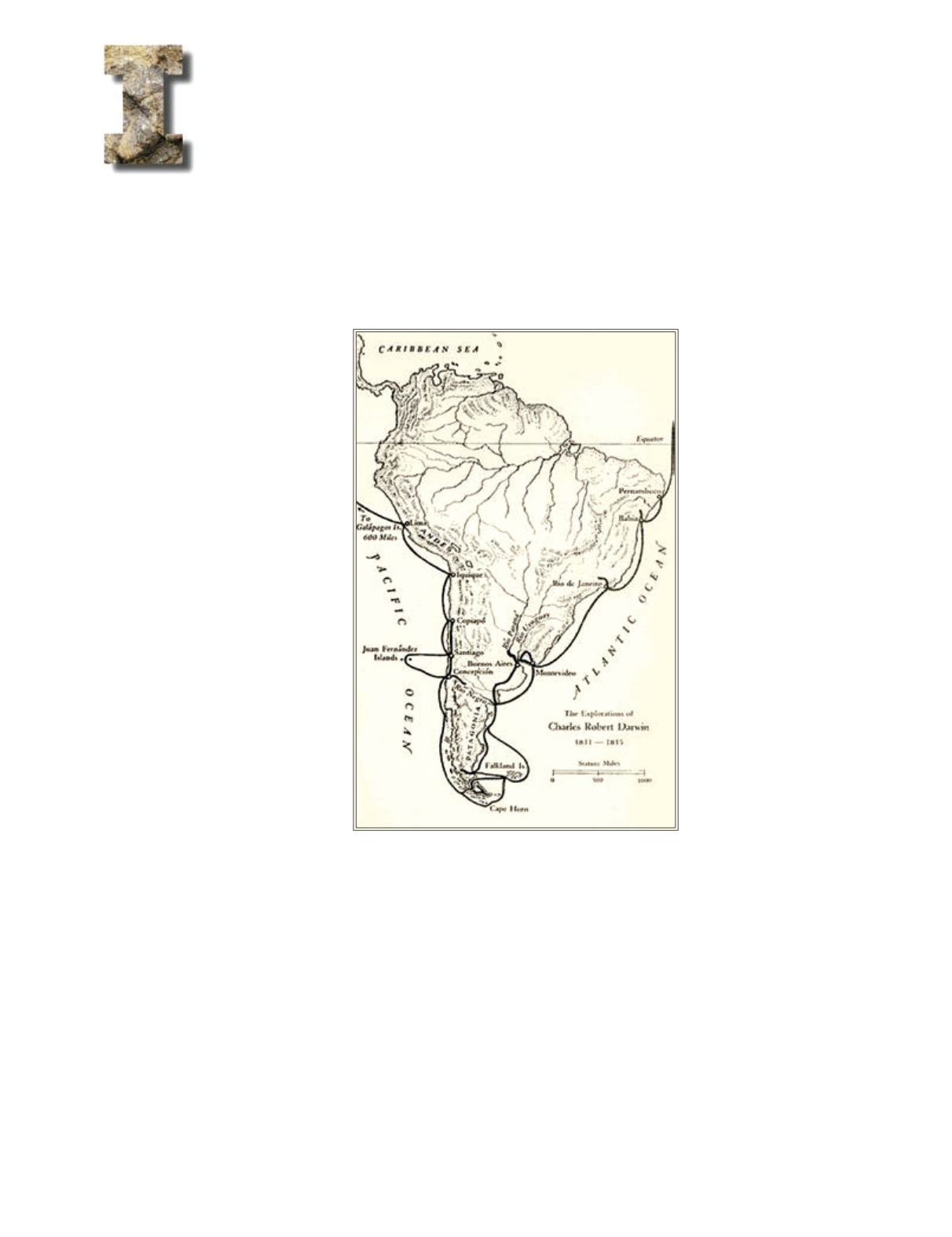

n 1984, as the 150th anniversary of Charles Darwin’s

journey to South America approached, a Chilean

friend and world-class sailor, Augustin Edwards,

invited me to be the navigator and geologist on a sail-

ing adventure following Darwin’s landfalls on the Chilean

coast. He said the BBC was planning a documentary, re-

tracing the voyage of the

HMS Beagle

. Edwards was making

replica ship’s boats and a replica of the 380-ton

Adventure

,

which accompanied the

Beagle

and was used to help sur-

vey the Argentine coast around Cape Horn and up the

coast of Chile into the Pacific. I jumped at the invitation.

My qualifications for

the journey were sparse.

I served as the assistant

navigator and the com-

munications officer on a

destroyer in the Vietnam

War and I had taken one

geology course at Hamilton

College my freshman year,

before transferring to Yale.

The choice of studying

geology was easy because

I was fascinated by how riv-

ers found channels through

solid rock, a phenomenon I

witnessed on several camp-

ing and canoeing trips of

over 100 miles on the Dela-

ware River as a lad. While

fishing, one is able to ob-

serve the natural world and

imagine how rocks, sedi-

mentary or metamorphic,

are bent by the stresses

of the mantle as it warps,

driven by the Earth’s plates

as they change position. I

could get lost in the ions of

time, having been shown

by my mother the trilobites and critters in rocks cut by

streams in Upstate New York.

So, with the offer in mind, I was off to the library to read

about the 21-year-old Darwin’s trip to South America as

a naturalist aboard the

HMS Beagle

, under the command

of 29-year-old Captain Robert FitzRoy. Darwin had little

training as a naturalist. He had collected beetles. He had

only gone to the mountains in Wales to “geologize” with

Adam Sedgwick, a professor of geology at Cambridge. He

had little knowledge of fossils, but there was a dearth of

fossil finds to compare at that time. He luckily had some-

how obtained a copy of Charles Lyell’s

Principles of Geology

in his kit. It is believed that his study of geology by read-

ing Lyell’s books and applying practical principles when

he saw oyster shells on top of mountains led him to con-

clusions that helped convince him of evolutionary theory.