Imagine SPS graduates given an all-expenses-paid

trip around the world during their budding university

experience. This was the introduction to science Ger-

many, England, France, and other countries gave their

students and professors during the Age of Discovery.

Instead of a one-term experience in Africa or Timbuktu,

such trips took years of hardship akin to the trips of

Captain James Cook with Mr. Joseph Banks as a botanist.

These trips were surrounded with the attendant wring-

ing of hands by the travelers’ families, wondering how

their loved ones would manage the hardship or whether

they would return to a career or marriage after such an

experience. Darwin proved not only to manage the hard-

ship; he became the most popular man on the ship – the

strongest and the friendliest. The other men nicknamed

him “Philos” for philosopher.

It turned out that the BBC declined to fund the com-

memorative documentary of Darwin’s journeys in South

America, forcing the cancellation of Mr. Edwards’s trip.

By that time, I was knee-deep in Darwin and had read

most of his writings. There was one story in his narrative

that caught my eye, of the era when explorers were seek-

ing the headwaters of rivers. Against Captain FitzRoy’s

better judgment, Darwin persuaded him to take 21 crew-

members and pull three ship’s boats by rope along the

shore against a six-knot current up the Rio Santa Cruz.

Darwin had learned by reading Lyell’s

Principles

of

Geology

that the Andes were the youngest mountain

range on the planet. He wanted to explore them and

learn more about their physical characteristics.

As Darwin recollects, the

Beagle

crew ran out of food

on the so-called “Plains of Disappointment” – well shy

of the Andes. The sorry group and depressed Darwin

turned around and went flying down the Rio Santa Cruz,

pushed by the melting flow of glaciers they had seen on

the snowcapped mountains. They returned in three days

to the careened

Beagle

at the Atlantic Ocean, with no

remaining provisions. Compelled by the desire to complete

the

Beagle

’s journey through Patagonia, I believed we

could do the same in much less time if we only went down-

stream. I rang up five pals, with whom I had done many

whitewater float trips in the American West, including

SPS formmates and annual fishing companions Sydney

Waud ’59 and John “Speedy” Mettler ’59.

All of the invited team members but Speedy Mettler

accepted the invitation to join the adventure. It was billed

as a float trip from the Andes to the Atlantic Ocean. I

investigated activities to keep the men occupied. I noted

in a foray to the Yale Geology Library that the “Plains of

Disappointment” (aptly named by Captain FitzRoy) were

within 10 kilometers of another river, La Leona, which

cut a deep valley and ultimately joined the Santa Cruz.

Yale maps indicated the geologic formations on either

side of the valley contained dinosaur-bearing soils. I wel-

comed the chance to scour the Earth for fragments of

these wondrous beasts. But, alas, the other team members

indicated they would travel with me from the Andes to the

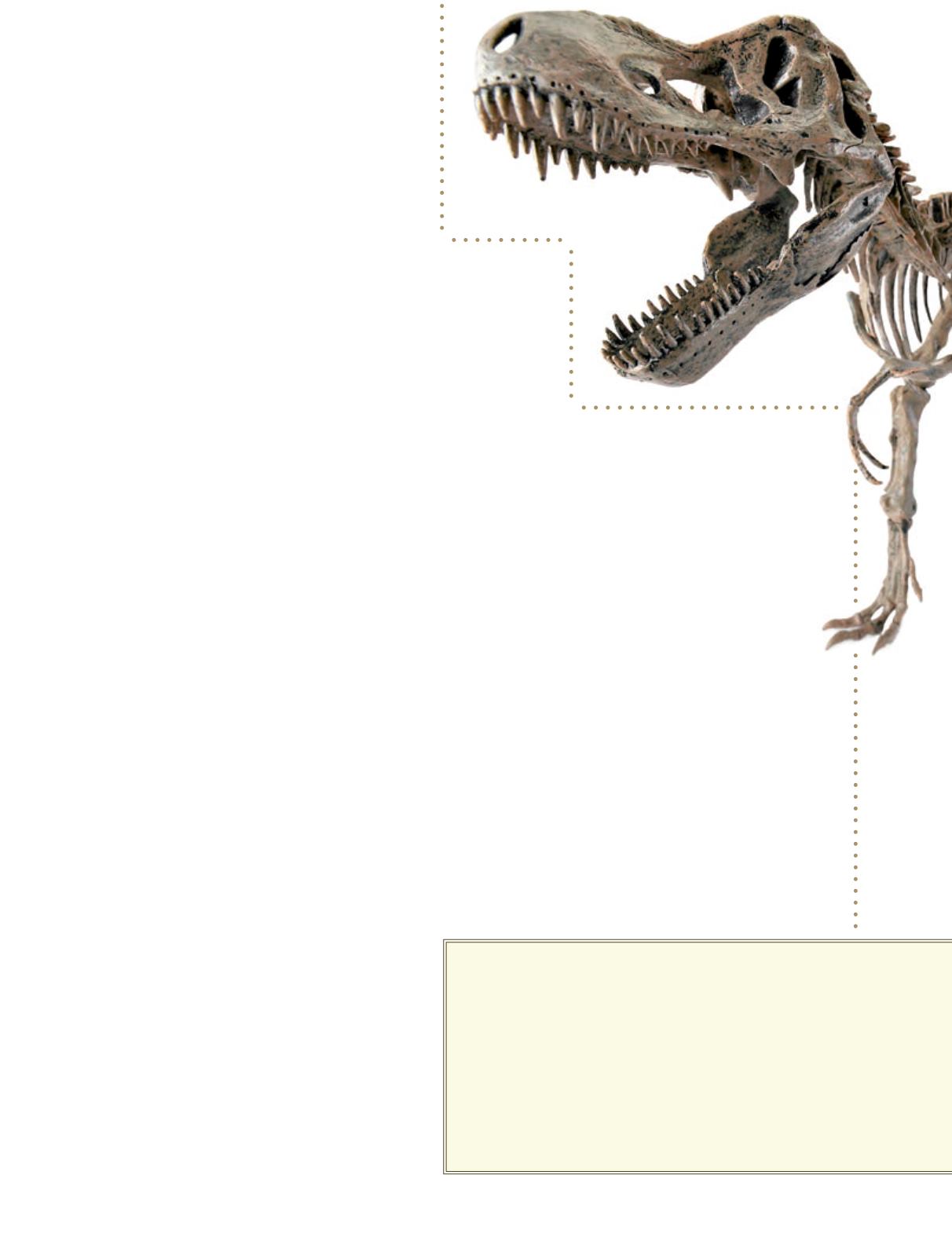

As a famous paleontologist once said “one

just looks down” and there they are on the

eroded surface. Most dinosaurs are found

by amateurs and, later, when professionals

hear about the discoveries, they dig them

up and report the finds as science.

Atlantic, but declined the chance to accompany me on my

quest for dinosaur bones.

On that trip in 1995, they afforded me three hours to

have a look, while they assembled the boats and gear. My

roommate from Yale, John Wilbur, a Navy Seal, actually

felt sorry for me because my crew revolted at looking for

dinosaur bones. At the last minute, he decided to accom-

pany me. We drove a short distance up a dirt road and

ascended an escarpment halfway up the La Leona. From

our elevated vantage point, we could see 50 square miles

of badlands, barren of any vegetation. It spread out before

us like a moonscape, inviting us to search for bones, but

our allotted time was exhausted and we returned to the

boats to go downstream.

My curiosity piqued by that initial observation, I’ve

been back to both sides of the La Leona Valley, looking

for bones with souls who are eager to go camping 200

miles north of the Straights of Magellan. In our weeks in

the boneyard, we have concentrated on the east side of

the La Leona Valley. When I say “we,” I’ve taken business

partner Chris Flagg, Syd Waud (multiple times), my son,

Erik ’87, my wife, an assortment of friends, and

actual

paleontologists. But for the paleontologists, we are all

amateurs, but that hasn’t stopped us from finding hund-

reds of bones. As a famous paleontologist once said “one