21

reform appeared to be on the horizon. But in 2003, the

EPA, now under the Bush administration, denied the

request, stating that it lacked authority to police green-

house gases because they weren’t “air pollutants” as

defined by the statute, citing the “scientific uncertainty”

of CO2 emissions’ effect on climate change as the basis

of its decision.

Enter Jim Milkey ’74

Around the same time as political tides shifted away

from climate reform in America, Jim Milkey was in

Denmark, taking a year off from the state Attorney

General’s Office to spend time with his wife, Cathie Jo

Martin, then a visiting professor at the University of

Copenhagen. Ironically, it was here – with an ocean and

nearly 4,000 miles separating him and Washington, D.C.

– that the nucleus of

Massachusetts v. EPA

materialized.

“[The trip to Denmark] gave me time to think; it gave

me a

way

to think,” Milkey recalled in a 2010 interview

with

Yale Climate Connections

. “In Europe, at the time,

global warming was not only the number one environ-

mental issue, it was really the only issue that people

wanted to talk about, the only environmental issue. And

it was on the radar screen there in a way that it just wasn’t

back in 2000 in America.”

The disparity was alarming. Milkey said in a recent

interview that he thought, “Oh my God, this is a big

problem. Why aren’t we doing anything about it?”

Ruminating on what he personally could do in his

position at the state Attorney General’s Office, an idea

began to crystallize.

“It became very obvious...that if anything was going

to happen in this sphere, it wasn’t going to be a result

of the federal government,” he says. So, in July 2001,

back on American soil, Milkey started building his case

with a single question: Could something be done on the

state level to force federal action on climate reform?

The concept had a particular resonance with Massa-

chusetts, where rising sea levels put the state’s nearly

200 miles of coastline at risk. In other words, the air

pollution from greenhouse gases and carbon dioxide

posed an undeniable threat to the Bay State. Remember

Section 202? It requires the EPA to set emission standards

for “any air pollutant...which in his judgment cause[s],

or contribute[s] to, air pollution which may reasonably

be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare.”

By refusing to regulate carbon dioxide and other green-

house gases, Milkey posited, the EPA was violating one

of the major tenets of the Clean Air Act.

Overcoming Obstacles

Formulating the legal argument was just the initial

hurdle in a series of many for Milkey, the first of which

was getting his boss, Massachusetts Attorney General

Thomas F. Reilly, to take the case. Milkey employed a

tactic that’s now proliferating among environmental

scientists and campaigners trying to communicate their

message to voters and make climate reform a political

priority – he made it personal.

“Tom Reilly believed strongly in protecting children,”

Milkey says. “We accurately sold the case to him as

coming down to one fundamental question: ‘What kind

of world do we want to leave to our children and grand-

children?’” Phrased that way, it didn’t take much more

convincing to get Reilly on board.

A recent Yale/Gallup/Clearvision poll found that,

while a large majority of Americans were personally

convinced that global warming is happening (71%),

they were evenly split on their level of worry about

global warming, with half personally worried either

a great deal (15%) or a fair amount (35%) and the

other half worried only a little (28%) or not at all (22%).

According to the study, these levels of personal worry

were due in part to the fact that many Americans

believe global warming is a serious threat to other

species, people, and places far away, but not so serious

of a threat to themselves, their own families, or local

communities.

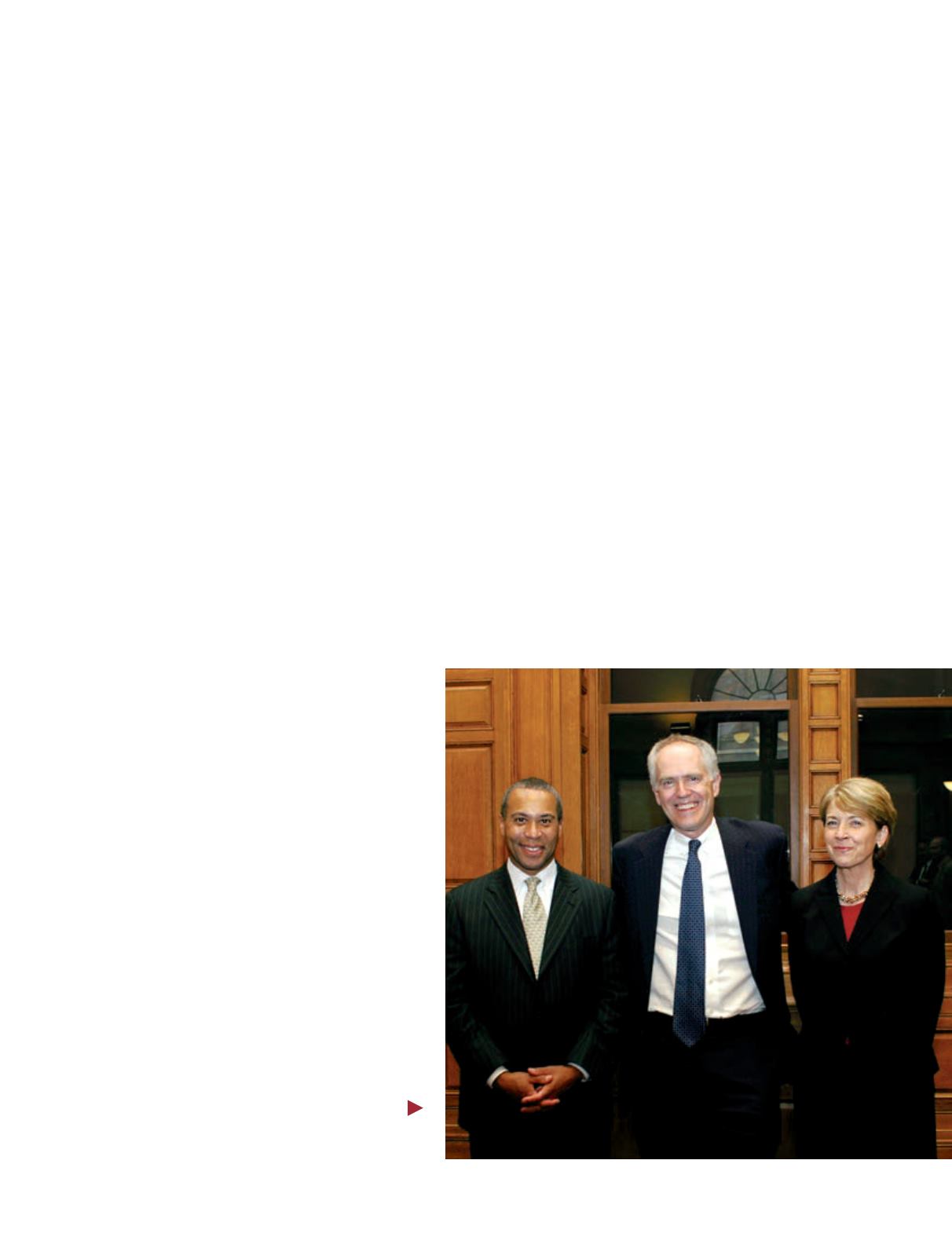

Milkey (c.), seen at his 2009 Massachusetts Appeals

Court swearing-in ceremony, stands with former

Mass. Governor Deval Patrick and former Mass.

Attorney General Martha Coakley.